By Margaret Deefholts

I am standing at the entrance to a splendid castle, its fireplace decorated with boughs of mistletoe and ivy, its hallway aglow with lights, and its grand staircase banisters wreathed in garlands of holly. The rich aroma of stuffed roast goose in a sage and onion gravy draws me to the dining room where distinguished guests exchange animated conversation across a table set in elegant style. The women wear silk gowns, their diamond necklaces winking in the light of candelabra centrepieces; the men sport mutton-chop moustaches and side-burns, and sip mulled wine from crystal goblets. A child’s laughter echoes faintly from one of the upstairs rooms. The ghosts of Christmases past still linger in the rooms of Craigdarroch Castle in Victoria, and although these guests at their Christmas banquet are figments of my imagination, the castle still celebrates this most joyous of all seasons by donning a mantle of dazzling Yuletide finery.

I am standing at the entrance to a splendid castle, its fireplace decorated with boughs of mistletoe and ivy, its hallway aglow with lights, and its grand staircase banisters wreathed in garlands of holly. The rich aroma of stuffed roast goose in a sage and onion gravy draws me to the dining room where distinguished guests exchange animated conversation across a table set in elegant style. The women wear silk gowns, their diamond necklaces winking in the light of candelabra centrepieces; the men sport mutton-chop moustaches and side-burns, and sip mulled wine from crystal goblets. A child’s laughter echoes faintly from one of the upstairs rooms. The ghosts of Christmases past still linger in the rooms of Craigdarroch Castle in Victoria, and although these guests at their Christmas banquet are figments of my imagination, the castle still celebrates this most joyous of all seasons by donning a mantle of dazzling Yuletide finery.

Today, in the drawing room on the entrance floor, a small girl, her eyes round with wonder, surveys a Christmas tree surrounded by antique toys, its branches arrayed in red ribbons, bows and silver ornaments. In Joan Dunsmuir’s first floor sitting room, the mantelpiece adorned with a satin hammock filled with pine cones, boughs of holly and silk tartan ribbons, draws an admiring ‘aaah’ from a group of Japanese visitors. Further along the corridor, a boy who is a dead ringer for Harry Potter—glasses and all—points out the curious looking brass speaking tube which once functioned as an intercom between this floor and the kitchens below. His younger sister waves an “I Spy” leaflet impatiently, wanting to continue her hunt of identifying treasures throughout the castle.

Craigdarroch Castle was completed in 1890 by coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, who spared no expense in furnishing his stately mansion with exquisite stained glass windows, oil paintings, and lavish Victorian furnishings. The family history, depicted in photos, memorabilia and information panels in the Exhibit Room on the second floor traces the lives of Robert and Joan Dunsmuir, their ten children and some of their grandchildren. The Dunsmuir progeny for the most part, however, seem to have been lonely, neurotic individuals, cursed rather than blessed by their inheritance.

Craigdarroch Castle was completed in 1890 by coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, who spared no expense in furnishing his stately mansion with exquisite stained glass windows, oil paintings, and lavish Victorian furnishings. The family history, depicted in photos, memorabilia and information panels in the Exhibit Room on the second floor traces the lives of Robert and Joan Dunsmuir, their ten children and some of their grandchildren. The Dunsmuir progeny for the most part, however, seem to have been lonely, neurotic individuals, cursed rather than blessed by their inheritance.

Hatley Castle, built by James Dunsmuir—the sole surviving son of Robert and Joan—is also in festive Christmas attire, and the entrance hall is cheery with twin Christmas trees flanking a fireplace. Festoons of evergreen boughs intertwined with poinsettias and twinkling lights lie across the mantelpiece.

James Douglas (not a ghostly revenant of the first Governor of British Columbia but a flesh-and-blood young man!) talks about Hatley Castle’s history and the Dunsmuir family’s quirks and foibles as he ushers me through the tastefully appointed rooms, each with its own distinctive wood panelling, and specially designed furnishings.

Although Hatley Castle’s Christmas decorations aren’t as elaborate as those at Craigdarroch, I am riveted by the wealth of anecdotal history surrounding the lives and times of James Dunsmuir’s family, much of it filled with tragedy—particularly the loss of an adored second son (and namesake) on the Lusitania during World War I. James’s daughters were “a wild lot…with energy and money to burn” according to a 2006 article in the Times Colonist newspaper.

Hatley Castle is haunted by ghosts of its past, and although stories of eerie occurrences abound, there are no easy explanations. Would one of these unhappy spirits be the sad alcoholic Dola, (James’ youngest daughter) who had a brief, unsuccessful marriage, and was then involved in a lifelong intimate relationship with actress Tallulah Bankhead? Who knows!

Leaving Victoria’s past and returning to its present, I stroll through the corridors of the Empress Hotel to admire sixty or more exquisitely decorated Christmas trees which are part of their annual Festival of Trees celebration. Sponsored by local businesses and organizations, to raise funds for the B.C. Children’s Hospital, it is a fitting commemoration of the Child born in Bethlehem and His ageless message of love and compassion.

Leaving Victoria’s past and returning to its present, I stroll through the corridors of the Empress Hotel to admire sixty or more exquisitely decorated Christmas trees which are part of their annual Festival of Trees celebration. Sponsored by local businesses and organizations, to raise funds for the B.C. Children’s Hospital, it is a fitting commemoration of the Child born in Bethlehem and His ageless message of love and compassion.

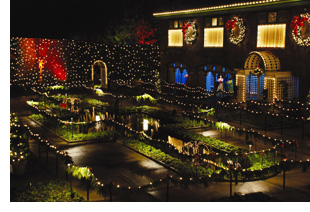

After a gourmet dinner at the Inn at Laurel Point’s Aura Restaurant a group of us are whisked away by stretch limousine into an enchanted fairyland—the Butchart Gardens in all their shimmering Christmas splendour. I am reduced to childlike awe at silver spangled trees, willow-the-wisp lights flickering through the bushes, avenues of lighted archways, ginger-bread type houses, and dancing “snow flakes” powdering the trees.

Each year, visitors have eagerly anticipated the newest addition to the Garden’s theme of the Twelve Days of Christmas, and we are fortunate enough to be here in the twelfth year when the carol’s complete set of ‘gifts’ are on display along the illuminated pathways. First up is the partridge in a pear tree, followed shortly after by two turtle doves nestling together, and so on… Particularly charming, however, are three French hens cavorting under a lighted Eiffel Tower, five golden rings floating on a lake and eight graceful maids a-milking. Turning a corner, we pause to watch a carousel with nursery rhyme and story book heroines twirling to the strains of music from the Nutcracker Suite, while a family with three children gleefully identify their favourite Mother Goose characters. At the end of our tour through fantasy-land, we are treated to a hearty rendition of Christmas favourites by a four-piece brass band.

But the evening isn’t over yet. Before boarding our limo under the gaze of twelve drummers marching overhead, our hosts from the Inn at Laurel Point offer us a choice of hot chocolate or eggnog beverages. I lift a mug of steaming hot, satiny smooth eggnog, laced with an out-of-this-world combination of rum and spices, and drink a toast to Victoria’s ghosts of Christmases past, and to its magical spirit of Christmas present.

But the evening isn’t over yet. Before boarding our limo under the gaze of twelve drummers marching overhead, our hosts from the Inn at Laurel Point offer us a choice of hot chocolate or eggnog beverages. I lift a mug of steaming hot, satiny smooth eggnog, laced with an out-of-this-world combination of rum and spices, and drink a toast to Victoria’s ghosts of Christmases past, and to its magical spirit of Christmas present.

If you go:

The Inn at Laurel Point is the epitome of luxury and attentive personalized service.

The Inn at Laurel Point is the epitome of luxury and attentive personalized service.

The rooms in the newly renovated Erickson Wing offer spectacular views from private balconies overlooking the harbour and a tranquil Japanese garden. The room décor is not only aesthetically pleasing with contemporary accents, natural colours, and plenty of natural light, but offers guests practical amenities such as an abundance of drawers and surfaces for personal belongings, desk space for laptop use, and excellent spot lighting around the room. Guests sink into cloud-soft beds and, as befits a world class hotel, they are pampered with body products by Molton Brown of London and Aveda.

The Inn’s elegant dining room, the Aura, features the culinary wizardry of Executive Chef, Brad Horen, nationally acclaimed as Canadian Chef of the Year by the Canadian Culinary Federation in 2007 and gold medalist at the 2008 Culinary Olympics in Efurt, Germany. Brad is modest and unassuming despite his towering achievements at both national and international levels. Wine pairings with each course, feature B.C. winery products and are expertly selected by Stuart Bruce, Restaurant Manager.

Few hotels can equal the quality of service offered by the Inn at Laurel Point, whether it be pampering guests with breakfast in bed, or their nightly turn-down room service that freshens the bathroom and plumps up pillows for bedtime. Visitors also enjoy complimentary wireless high speed Internet connections and access to movies on demand.

It doesn’t come much better!

For more information go to www.laurelpoint.com

Craigdarroch Castle: www.craigdarrochcastle.com/ offers their Christmas programme schedule at www.craigdarrochcastle.com/pdf/web_calendar_08_.pdf

Hatley Castle is located on the grounds of Royal Roads Military College and Royal Roads University. Detailed information (including a map and entrance rates) as well as their Christmas programmes may be accessed via their comprehensive website at www.hatleycastle.ca

Festival of Trees at the Fairmont Empress:

blog.vancouverisland.travel/2007/11/15/festival-of-trees-tour-tea/

www.tourismvictoria.com/Content/EN/436.asp?id=3216

Butchart Gardens:

The Magic of Christmas: www.butchartgardens.com/christmas

Home page: www.butchartgardens.com

About the Author:

This week Traveling Tales welcomes Margaret Deefholts, an author and freelance travel writer who lives in Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver B.C. Learn more about Margaret at her website www.margaretdeefholts-journeys.com

About The Photos:

1. Craigdarroch Castle: Margaret Deefholts

2. Hatley Castle: Winter Wonderland – Photo: Courtesy Hatley Castle

3. Festival of Trees, The Empress Hotel: Margaret Deefholts

4. Butchart Gardens: Photo Courtesy of “The Butchart Gardens Ltd., Victoria, B.C.”

5. Alcove in glass fronted banquet hall at the Inn at Laurel Point: Margaret Deefholts

What’s one thing that most people hope for when planning a vacation? Good weather, right? It’s always top priority on my travel wish list. So, as we load onto the BC ferry, bound for Langdale, my spirits literally dampen when pellet-size droplets spill from the swollen skies.

What’s one thing that most people hope for when planning a vacation? Good weather, right? It’s always top priority on my travel wish list. So, as we load onto the BC ferry, bound for Langdale, my spirits literally dampen when pellet-size droplets spill from the swollen skies.  Even though it’s just minutes from the grid, Sakinaw Lake Lodge feels blissfully removed from civilization. We’re whisked away by an African Queen-like pontoon boat to the far side of the lake where it snuggles into the forested hillside. Two of the guest sanctuaries cantilever over lapping waves. The main cozy cottage that sleeps three, boasts an all-equipped kitchen and the penthouse tent house depicts glamping to a tee. Chiropractic queen beds, crisp Egyptian cotton duvets, comfy Fretted bathrobes –this is my kind of camping!

Even though it’s just minutes from the grid, Sakinaw Lake Lodge feels blissfully removed from civilization. We’re whisked away by an African Queen-like pontoon boat to the far side of the lake where it snuggles into the forested hillside. Two of the guest sanctuaries cantilever over lapping waves. The main cozy cottage that sleeps three, boasts an all-equipped kitchen and the penthouse tent house depicts glamping to a tee. Chiropractic queen beds, crisp Egyptian cotton duvets, comfy Fretted bathrobes –this is my kind of camping!  The property is a labor of love for Garrett and Liza Gabriel, and Garrett’s mother, Donna. “We each have our preferences and talents,” Liza shares. “Donna has the green gardener’s thumb, Garret is the wine guy and I do most of the cooking.”

The property is a labor of love for Garrett and Liza Gabriel, and Garrett’s mother, Donna. “We each have our preferences and talents,” Liza shares. “Donna has the green gardener’s thumb, Garret is the wine guy and I do most of the cooking.”  Jervis Inlet bisects the upper and lower sections of the Sunshine Coast and BC Ferries bridges them together. Our fifty minute scenic cruise is more like a National Geographic slide show and from front row seats the rolling vistas include quiet inlets, lush finger-like fjords and jagged peaks.

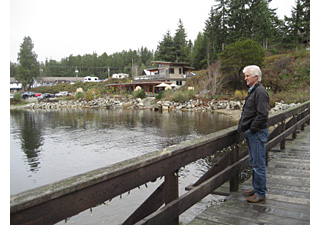

Jervis Inlet bisects the upper and lower sections of the Sunshine Coast and BC Ferries bridges them together. Our fifty minute scenic cruise is more like a National Geographic slide show and from front row seats the rolling vistas include quiet inlets, lush finger-like fjords and jagged peaks.  The quaint historical fishing village of Lund, founded by the Thulin brothers in 1889, is also the gateway to Desolation Sound. Along with remnants of the Swedish heritage it oozes lots of charm and allure. A boardwalk flanked by a handful of shops and eateries trails down to the hull-filled marina. Whether it’s waiting for the fresh catch to come in or a tour boat to go out, there’s never a dull moment.

The quaint historical fishing village of Lund, founded by the Thulin brothers in 1889, is also the gateway to Desolation Sound. Along with remnants of the Swedish heritage it oozes lots of charm and allure. A boardwalk flanked by a handful of shops and eateries trails down to the hull-filled marina. Whether it’s waiting for the fresh catch to come in or a tour boat to go out, there’s never a dull moment.  In the adjacent dining room mealtime magic happens three times a day. Our palates are pleased after the chef savvy line-up; beautifully executed crab cakes precede Sevilla Island Seafood Boats, Ian’s sensational creation of roasted squash that brims over with scallops, salmon, and prawns. After being paired with fine wine it’s topped off with a decadent dessert. We also discover that the breakfasts are just as grand: melt in your mouth blueberry scones and homemade preserves, followed by hearty entrees –ranging from anything and everything omelets to fluffy French toast. Ian and Donna believe a hearty meal is an important start to the day. And in order to check out the abundant sea life that thrives below the lapping waves, you’ll want to be energized.

In the adjacent dining room mealtime magic happens three times a day. Our palates are pleased after the chef savvy line-up; beautifully executed crab cakes precede Sevilla Island Seafood Boats, Ian’s sensational creation of roasted squash that brims over with scallops, salmon, and prawns. After being paired with fine wine it’s topped off with a decadent dessert. We also discover that the breakfasts are just as grand: melt in your mouth blueberry scones and homemade preserves, followed by hearty entrees –ranging from anything and everything omelets to fluffy French toast. Ian and Donna believe a hearty meal is an important start to the day. And in order to check out the abundant sea life that thrives below the lapping waves, you’ll want to be energized.  Lund’s Terracentric Coastal Adventures also provides tours above and beneath the deep, and on our final day we venture out on a zodiac, with high hopes of spotting some sea life. The sky looks ominous and dark bulbous clouds threaten rain. Once again my fingers are crossed for a little bit of luck.

Lund’s Terracentric Coastal Adventures also provides tours above and beneath the deep, and on our final day we venture out on a zodiac, with high hopes of spotting some sea life. The sky looks ominous and dark bulbous clouds threaten rain. Once again my fingers are crossed for a little bit of luck.  Terracentric believes that we’re all connected to our natural environment and our guide Christine Hollmann has a wonderful way of integrating eco-education with the stunning surroundings. While paralleling the mainland, we learn about the First Nations people and explorer Captain Vancouver. In shallow bays she shares the symbiotic relationship between otters, sea urchins and kelp. And when checking out lazy sun-bathing seals we discover the importance of keeping our distance. This act of privacy is a guideline that Christine closely adheres to and though we never invade their personal space, we’re able to get a real good glimpse of the sea life that abounds.

Terracentric believes that we’re all connected to our natural environment and our guide Christine Hollmann has a wonderful way of integrating eco-education with the stunning surroundings. While paralleling the mainland, we learn about the First Nations people and explorer Captain Vancouver. In shallow bays she shares the symbiotic relationship between otters, sea urchins and kelp. And when checking out lazy sun-bathing seals we discover the importance of keeping our distance. This act of privacy is a guideline that Christine closely adheres to and though we never invade their personal space, we’re able to get a real good glimpse of the sea life that abounds.  As we’re heading back, we have one last performance –a grand finale off to the distant starboard. Jet black torsos break the still surface, revealing their pure white undercarriages before submerging again. They swim at record speeds, darting back and forth, leaping and cresting in unison, creating a riot of rooster tail spray. Though it’s just a feeding frenzy to these Dall’s Porpoise, it’s a synchronized water ballet to us. And as rays of sun slice through the cloudy overcast sky, another wish is granted. The Sunshine Coast –it’s a destination of eco excellence whatever the weather!

As we’re heading back, we have one last performance –a grand finale off to the distant starboard. Jet black torsos break the still surface, revealing their pure white undercarriages before submerging again. They swim at record speeds, darting back and forth, leaping and cresting in unison, creating a riot of rooster tail spray. Though it’s just a feeding frenzy to these Dall’s Porpoise, it’s a synchronized water ballet to us. And as rays of sun slice through the cloudy overcast sky, another wish is granted. The Sunshine Coast –it’s a destination of eco excellence whatever the weather!

This is also a story of humiliation. A dark time in our history when racism flourished like a parasitic flower watered by discrimination and injustice. In an effort to discourage Chinese from coming to these shores, a head tax of $50 was applied (an enormous sum in those days), and when that failed to have the desired effect, it was increased to $500. It meant that many men weren’t able to afford to bring their wives and children to Canada, and spent whatever leisure time they had hanging out in bars and gambling dens, their loneliness tempered only by the oblivion of the opium pipe, and the consolation of prostitutes. They worked hard, but the lure of easy money on the gambling circuit meant that they often lost hard too.

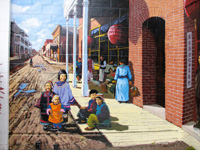

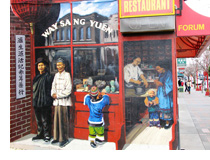

This is also a story of humiliation. A dark time in our history when racism flourished like a parasitic flower watered by discrimination and injustice. In an effort to discourage Chinese from coming to these shores, a head tax of $50 was applied (an enormous sum in those days), and when that failed to have the desired effect, it was increased to $500. It meant that many men weren’t able to afford to bring their wives and children to Canada, and spent whatever leisure time they had hanging out in bars and gambling dens, their loneliness tempered only by the oblivion of the opium pipe, and the consolation of prostitutes. They worked hard, but the lure of easy money on the gambling circuit meant that they often lost hard too. On Fisgard, Adams pauses before mural of this very same street, back in the 1880s. It portrays a squelchy mud road, flanked by houses with wooden balconies, and the artist has prettied it up by including kids and women – none of whom, according to Adams would have been there at the time. The adjoining mural depicting Way Sang Yuen’s herbalist shop is no longer there (it’s now in the Burnaby Village Museum) but today’s Chinatown still boasts herbalists galore. I drop into one just a few steps away, and am engulfed by a completely

On Fisgard, Adams pauses before mural of this very same street, back in the 1880s. It portrays a squelchy mud road, flanked by houses with wooden balconies, and the artist has prettied it up by including kids and women – none of whom, according to Adams would have been there at the time. The adjoining mural depicting Way Sang Yuen’s herbalist shop is no longer there (it’s now in the Burnaby Village Museum) but today’s Chinatown still boasts herbalists galore. I drop into one just a few steps away, and am engulfed by a completely  different world. The room is cramped, the glass display case filled with gnarled roots, twigs, seeds and other esoteric medicinal potions, labeled in Chinese. The herbalist doctor has a line up of people to meet with him, so I content myself with watching his assistant weigh several bundles of leaves and pound them in a mortar and pestle. She speaks no English, but smiles broadly. Her little girl offers me her kitten to stroke.

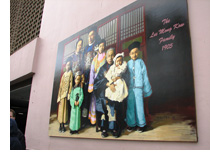

different world. The room is cramped, the glass display case filled with gnarled roots, twigs, seeds and other esoteric medicinal potions, labeled in Chinese. The herbalist doctor has a line up of people to meet with him, so I content myself with watching his assistant weigh several bundles of leaves and pound them in a mortar and pestle. She speaks no English, but smiles broadly. Her little girl offers me her kitten to stroke. Probably the most illustrious “Lee” in Chinatown is featured on a mural directly opposite the Chinese Public School. Lee Mong Kow was a dynamic business entrepreneur, a dedicated champion of his Chinese brethren (he acted as a go-between between the Chinese and Canadian bureaucracy) and a tireless social worker. He somehow also managed to find time (and energy!) to sire seventeen children, thirteen of whom survived to adulthood.

Probably the most illustrious “Lee” in Chinatown is featured on a mural directly opposite the Chinese Public School. Lee Mong Kow was a dynamic business entrepreneur, a dedicated champion of his Chinese brethren (he acted as a go-between between the Chinese and Canadian bureaucracy) and a tireless social worker. He somehow also managed to find time (and energy!) to sire seventeen children, thirteen of whom survived to adulthood. Adams takes us via Lee Mong Kow Way to Centennial Square once part of Cormorant Street, the very centre of old Chinatown. A few high class brothels flanked the street as did an opium factory. Opium was legal then; gambling however was not!

Adams takes us via Lee Mong Kow Way to Centennial Square once part of Cormorant Street, the very centre of old Chinatown. A few high class brothels flanked the street as did an opium factory. Opium was legal then; gambling however was not! burned (along with joss sticks) at funerals to ensure that the spirits of the departed are comfortable and have money to spend in the afterlife. This is a prelude to the most fascinating of all subjects on this tour—the traditions and rites which shaped Chinese lives, not just then, but also today. Adams is a superb raconteur, and his perceptive insights shed light on Eastern beliefs that stand in contrast to our pragmatic Western outlook.

burned (along with joss sticks) at funerals to ensure that the spirits of the departed are comfortable and have money to spend in the afterlife. This is a prelude to the most fascinating of all subjects on this tour—the traditions and rites which shaped Chinese lives, not just then, but also today. Adams is a superb raconteur, and his perceptive insights shed light on Eastern beliefs that stand in contrast to our pragmatic Western outlook. A highlight of the tour is Fan Tan Alley, a narrow lane running like a crack between red two-storey brick buildings. Despite the souvenir shops and trendy clothing racks lining the alleyway, there is much that evokes a sense of the past—secret gambling and opium dens that flourished above the alley and its maze of tributary lanes. Chinese signage mark entrances to hidden courtyards such as the one where Adams gives us a quick demonstration of how to play Fan Tan, the popular gambling pastime from which the alleyway derives its name. A red wooden door carrying the number 23 ½ denotes a mezzanine residential apartment tucked in between floors—at one time it probably housed several men rooming together to save money. Like Fan Tan Alley, Dragon Alley on the north side of Fisgard street, was also a secluded labyrinthine neighbourhood.

A highlight of the tour is Fan Tan Alley, a narrow lane running like a crack between red two-storey brick buildings. Despite the souvenir shops and trendy clothing racks lining the alleyway, there is much that evokes a sense of the past—secret gambling and opium dens that flourished above the alley and its maze of tributary lanes. Chinese signage mark entrances to hidden courtyards such as the one where Adams gives us a quick demonstration of how to play Fan Tan, the popular gambling pastime from which the alleyway derives its name. A red wooden door carrying the number 23 ½ denotes a mezzanine residential apartment tucked in between floors—at one time it probably housed several men rooming together to save money. Like Fan Tan Alley, Dragon Alley on the north side of Fisgard street, was also a secluded labyrinthine neighbourhood. Although the Chinatown Walking tour with John Adams ends at the Gate of Harmonious Interest, he offers to accompany those of us who are interested in taking a look at the oldest Chinese temple in Chinatown. Housed in the topmost floor of the Yen Wo Society building across the street, the Tam Kung temple is worth the climb of 51 steps.

Although the Chinatown Walking tour with John Adams ends at the Gate of Harmonious Interest, he offers to accompany those of us who are interested in taking a look at the oldest Chinese temple in Chinatown. Housed in the topmost floor of the Yen Wo Society building across the street, the Tam Kung temple is worth the climb of 51 steps. A patron saint of seafarers, Tam Kung’s statue is resplendent in red and gold brocade robes, set within an elaborate gilt framework which glows in the light of candles. Ornate silk processional flags and banners cover the walls, and the altar is laden offerings of fruit and flowers. Few devotees are here this morning, and the temple is tranquil, the only sound being the muffled ‘whoosh’ of traffic wafting up from Government Street. Adams talks about Eastern beliefs in predestined fate, and the search for answers to questions, obtained by tossing small wooden tokens, or the process of vigorously shaking bamboo sticks in a container, to reveal coded messages predicting health and prosperity, or the lack of it.

A patron saint of seafarers, Tam Kung’s statue is resplendent in red and gold brocade robes, set within an elaborate gilt framework which glows in the light of candles. Ornate silk processional flags and banners cover the walls, and the altar is laden offerings of fruit and flowers. Few devotees are here this morning, and the temple is tranquil, the only sound being the muffled ‘whoosh’ of traffic wafting up from Government Street. Adams talks about Eastern beliefs in predestined fate, and the search for answers to questions, obtained by tossing small wooden tokens, or the process of vigorously shaking bamboo sticks in a container, to reveal coded messages predicting health and prosperity, or the lack of it.

Two things never cease to delight me: firstly, the splendour of our British Columbia scenery, and secondly, the exhilaration of train travel. Today, I’m about to enjoy both on a journey aboard the Whistler Mountaineer.It is a surprisingly chilly and pale July morning, but that does nothing to dampen the anticipation of the crowd gathered at the railway station in North Vancouver. Kids jump up and down gleefully, and parents and grandparents help themselves to complimentary coffee while awaiting the “All Aboard” call.

Two things never cease to delight me: firstly, the splendour of our British Columbia scenery, and secondly, the exhilaration of train travel. Today, I’m about to enjoy both on a journey aboard the Whistler Mountaineer.It is a surprisingly chilly and pale July morning, but that does nothing to dampen the anticipation of the crowd gathered at the railway station in North Vancouver. Kids jump up and down gleefully, and parents and grandparents help themselves to complimentary coffee while awaiting the “All Aboard” call. And then comes the big “Aaaah!” of the journey—the spectacular Cheakamus Canyon. For travellers on the Whistler Mountaineer, this sight alone is worth the price of admission. We run along its lip, as the river boils and foams, far, far below us, forcing its way through narrow channels and erupting around bends.

And then comes the big “Aaaah!” of the journey—the spectacular Cheakamus Canyon. For travellers on the Whistler Mountaineer, this sight alone is worth the price of admission. We run along its lip, as the river boils and foams, far, far below us, forcing its way through narrow channels and erupting around bends. At Whistler, the chill of the morning has given way to brilliant sunshine and the village is filled with holiday crowds: teens on bikes, young couples hand in hand, and families with toddlers in tow.

At Whistler, the chill of the morning has given way to brilliant sunshine and the village is filled with holiday crowds: teens on bikes, young couples hand in hand, and families with toddlers in tow. The tangerine sun begins its daily departure. To our left looms a thick backdrop of old growth evergreens. To our right, clear waves tumble at our feet. Dusk settles over smooth charcoal coloured sand as we walk, hands clutched, we’re awed by the breathtaking view. Tofino. It’s no ordinary place.

The tangerine sun begins its daily departure. To our left looms a thick backdrop of old growth evergreens. To our right, clear waves tumble at our feet. Dusk settles over smooth charcoal coloured sand as we walk, hands clutched, we’re awed by the breathtaking view. Tofino. It’s no ordinary place. Hot Springs Cove is so captivating we almost miss our flight, and although jelly-legged and breathless after the race back, we make it just in time for our Tofino Air take off.

Hot Springs Cove is so captivating we almost miss our flight, and although jelly-legged and breathless after the race back, we make it just in time for our Tofino Air take off. “Good morning,” Cal whispers, as we wake for our final and most exhilarating day. Surfing is unlike any sport. Step foot in the Pacific and you’ll understand. White water swirls around our raven rubber ankles as we watch the wild untamed swell.

“Good morning,” Cal whispers, as we wake for our final and most exhilarating day. Surfing is unlike any sport. Step foot in the Pacific and you’ll understand. White water swirls around our raven rubber ankles as we watch the wild untamed swell.