by Patricea Chow-Capodieci

When planning our holiday in Thailand, my husband had exclaimed excitedly,

“Let’s go and see the Kanchanaburi tigers. It will be fun!” I love an adventure and had enthusiastically agreed that meeting these majestic beasts would be an awesome experience.

Yet when I eventually laid eyes on the tigers, my excitement was replaced with nervousness and my mind was saying: “This would really be an experience, if I live to relate it!”

Yet when I eventually laid eyes on the tigers, my excitement was replaced with nervousness and my mind was saying: “This would really be an experience, if I live to relate it!”

Eight tigers lay motionless on the ground of the Tiger Canyon, within the premises of the Watpa Luangta Ba Yannasampanno Forest Monastery, commonly known as Tiger Temple. The nearest tiger was about three meters from me. Except for their breathing movements, the octet seemed as if they were asleep yet ready to spring up and counter an unexpected attack.

Unlike at conventional zoos where visitors admire tigers from behind the safety of a moat surrounding the mammals’ enclosure, visitors to the Tiger Temple, can sit next to, and have pictures taken with the tigers in the Tiger Canyon.

The thrill of being so close to these beasts was slightly numbed by the fact that the only restrain on the tigers is a leash around their neck, attached to a metal chain and affixed to the ground.

Linking her left arm through my right arm, a volunteer guided me toward the rear of the closest tiger. As I crouched for my picture to be taken, I kept my eyes on the tiger, wondering if it could sense my presence.

Linking her left arm through my right arm, a volunteer guided me toward the rear of the closest tiger. As I crouched for my picture to be taken, I kept my eyes on the tiger, wondering if it could sense my presence.

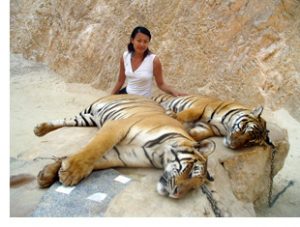

I was next led to sit behind two tigers lying on their left side atop a flat rock. Slightly smaller than the previous tiger, it seemed as if they had slowly lain their exhausted bodies down to slumber. The tiger on the left was lightly resting its front right paw on the back of the other tiger, much like a reassuring touch from one sibling to another.

I gingerly placed my left hand on the first tiger; the beast hardly moved. This time, I managed to smile into the camera, before I was taken to the next tiger lying on the ground.

As I approached the largest tiger that I would be next to, a volunteer gave it what appeared to be a chest rub. This caused the tiger to calmly turn and stretch out on its back with its paws in the air, before resuming its previous motionless state with its eyes shut. I was startled by what happened, as I had assumed that the tigers would not welcome any disturbance.

As my camera captured me crouching beside its beautiful form, I was tempted to touch its hind paws, yet I was afraid the action would cause unexpected movement.

I could not act on the temptation as my time with the tigers ended. I went back to the waiting area while my camera went for a second round, capturing my husband’s turn with the tigers. I stood silently, reflecting on my amazing experience with the tigers as I watched my husband happily stroking the tigers as he would our pet dog, while beaming widely for the camera.

Later, we would learn that the tigers were led out of their cages to the canyon only in the afternoon between 3.30pm and 5pm. In the past, they were allowed to roam freely on the temple grounds but as the number of visitors increased, the tigers also became more irritable.

Thus they were kept caged when they were not meeting visitors in the canyon. As they are nocturnal animals, the tigers sleep during the heat of the day, which is what they appear to be doing in the canyon.

The current adult tigers were brought to the temple as cubs by villagers, mostly orphaned when their parents were killed by poachers. The first cub was brought here in 1995.

Out of compassion, abbot Pra Acharn Phusit (Chan) Kantitharo cared for the injured cub, together with the other wild animals including water buffalo, goat, hog, boar, red jungle fowl, pea fowl and deer, that came to the forest temple and sanctuary in 1994.

Out of compassion, abbot Pra Acharn Phusit (Chan) Kantitharo cared for the injured cub, together with the other wild animals including water buffalo, goat, hog, boar, red jungle fowl, pea fowl and deer, that came to the forest temple and sanctuary in 1994.

Through the years, some female tigers have given birth to cubs at the temple. As of 2006, 10 tiger cubs have been born at the temple, bringing the total number of tigers to 18.

The tigers are given dried cat food, cooked whole chicken, and cooked beef, ensuring that they do not taste blood and thus associate blood with meat. The monks feed, groom and handle the tigers, so the tigers are accustomed to human presence and unfamiliar with violence.

While the cubs can roam free within a reserve in future, the adults will spend their days with the monks. Therefore, construction on a bigger enclosure for the tigers is currently underway at the temple.

To date, the Tiger Temple has survived solely on alms and donations collected from the public. The enclosure’s construction means additional funds are required, thus there is now an entrance fee of 300 baht (approximately US$9.25), that visitors should consider as a minimum donation to the temple.

A third of this amount goes toward the building fund while the rest offsets the daily food, upkeep and medical attention required by the tigers.

The sun begins its slow descent as I leave the Tiger Temple, still awed by my close encounter with the few tigers and touched by the monks’ compassion for the beasts.

I turn to my husband and firmly state that we will come back to visit the tigers every year until they are housed in their new enclosure. It is a promise that we hope others can fulfill with us too.

About the author:

This week Traveling Tales welcomes freelance travel writer Patricea Chow-Capodieci who lives in Singapore. Check her website at www.pizzazz-words.com

Photos by Patricea Chow-Capodieci:

1: An overview of the Tiger Canyon.

2: The author sits with a couple of tigers.

3: A variety of animals wander the Temple grounds.

About Wat Pa Luang Ta Ba Yannasampanno Forest Monastery

The temple is located at Saiyok District, Kanchanaburi Province, 71150, Thailand. It is open to visitors from 1pm to 5pm daily. Visitors can get close to the tigers at the Tiger Canyon from 3.30pm to 5pm.

There is an entrance fee of 300 baht (approximately US$9.25). Visitors are welcome to donate additional sums or purchase a variety of souvenirs. All proceeds go toward the fund for New Home for Tigers Project and daily expenditure for the care of the tigers.

Visitors are reminded not to don bright colours, such as red, pink or orange for they will not be allowed in to the Tiger Canyon. Ladies are reminded that this is a visit to a monastery, so please dress appropriately. A safe gauge is to ensure that your knees are covered and your top/blouse is not too revealing. Flash photography is not permitted in the Tiger Canyon.

Getting to Wat Pa Luang Ta Ba Yannasampanno Forest Monastery from Bangkok

By bus:

Take a bus from the Southern Bus Terminal in Bangkok to Kanchanaburi. The trip costs approximately 100 baht (approximately US$3) and lasts around three hours. At the Kanchanaburi bus station, take bus number 8203 heading toward Sai Yok. Ask the bus driver to stop at the temple, Wat Pa Luang Ta Ba Yannasampanno. This trip costs 25 baht (approximately US$0.75) and takes about 45 minutes. Alighting at the bus stop, follow the dirt road to the front gate of the temple. This is about 1.5km (slightly less than a mile) and takes about half an hour to 40 minutes.

By taxi:

Ask the taxi driver to bring you to the temple, Watpa Luangta Ba Yannasampanno. It will cost between 200 to 250 baht (approximately US$6 to US$8) and take about half an hour.

I wonder if Ernest Hemingway strolled down this same route when he spent time here while recovering from an illness, and what were the sights he saw then that inspired him to pen his novel, Across the River and Into the Trees.

I wonder if Ernest Hemingway strolled down this same route when he spent time here while recovering from an illness, and what were the sights he saw then that inspired him to pen his novel, Across the River and Into the Trees. My attention is immediately drawn to the red brick wall we had arrived at, standing about 10 meters from the stone throne.

My attention is immediately drawn to the red brick wall we had arrived at, standing about 10 meters from the stone throne.

The river was renamed from Mae Klong in the 1960s, after the bridge was made famous by the 1957 movie, The Bridge On the River Kwai. The latter was based on the novel The Bridge Over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle, set against the building of the bridge as part of the Burma Railway.

The river was renamed from Mae Klong in the 1960s, after the bridge was made famous by the 1957 movie, The Bridge On the River Kwai. The latter was based on the novel The Bridge Over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle, set against the building of the bridge as part of the Burma Railway. Our journey would continue further along the Death Railway, with a ride on a passenger train up to Nam Tok station, beyond which the railway line was dismantled by the State Railway of Thailand in 1947.

Our journey would continue further along the Death Railway, with a ride on a passenger train up to Nam Tok station, beyond which the railway line was dismantled by the State Railway of Thailand in 1947.