by Chris Millikan

When touring China’s legendary sights with twenty other enthusiasts, my husband and I encountered unimagined marvels in Xian, the old capital where early Emperors ruled for 3000 years. Two amazing days began high atop ramparts of the ancient city wall, one of few remaining in China.

When touring China’s legendary sights with twenty other enthusiasts, my husband and I encountered unimagined marvels in Xian, the old capital where early Emperors ruled for 3000 years. Two amazing days began high atop ramparts of the ancient city wall, one of few remaining in China.

On the way to the north gate, our energetic guide Hanson exclaimed, pointing, “That Bell Tower’s from the 14th-century…its huge bell once signaled sunrise every morning. To the west, that evening Drum Tower would sound day’s end.”

Along some of the nine impressive wall miles circling the city, we strolled above the moat. Built over 600 years ago for protection and food storage, formidable watchtowers solidly anchored each corner, smaller defensive towers dotting the top. Fluttering crimson flags and lanterns accentuated the stark gray structure.

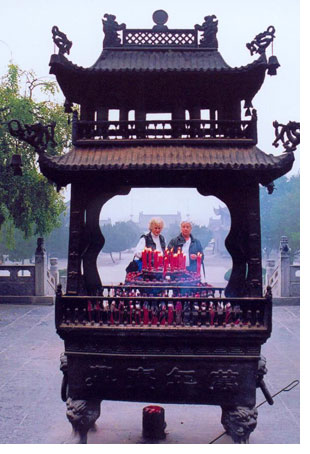

We next arrived at a religious complex built on the city’s southern edge about 652AD. Silver morning mists shrouded its peaceful gardens as Hanson regaled us with the curiously named sanctuary’s legend, “During a severe famine, Buddha miraculously provided flocks of wild geese to feed the starving worshippers…” Nowadays, forty Buddhist monks live at Great Wild Goose Pagoda, once housing 300 in 2,000 rooms.

We next arrived at a religious complex built on the city’s southern edge about 652AD. Silver morning mists shrouded its peaceful gardens as Hanson regaled us with the curiously named sanctuary’s legend, “During a severe famine, Buddha miraculously provided flocks of wild geese to feed the starving worshippers…” Nowadays, forty Buddhist monks live at Great Wild Goose Pagoda, once housing 300 in 2,000 rooms.

Pausing to light slender red candles and bundles of incense-sticks, we sent silent wishes and prayers to our loved ones back home before entering the soaring seven-story pagoda protecting Buddhist scriptures. Hanson explained, “Renowned traveling monk Xuan Zang brought these sacred writings from India along the Ancient Silk Road and translated them into these 1335 volumes kept in all these glassed cabinets.”

After wandering lively afternoon markets in the Muslim quarter, we stopped at the Great Mosque, today serving over 60,000 Chinese Muslims. Hanson infused us with its history, “Founded in 742, this was first the religious center for Arab merchants. Then, when Kublai Khan expanded westward in the 13th century, large numbers of Muslim soldiers and artisans resettled in China.” Except for intricate Arabic lettering, the beautiful wooden building looked entirely Chinese, its two-story pagoda replacing typical domes and minarets.

Just when we thought it couldn’t get any better, we arrived at Xian’s Grand Opera House, a huge dinner-theatre. Soon, white-clad servers delivered basket-after-steaming-basket of tiny, mouthwatering dumplings. Washing them down with cold Chinese beer and wielding our chopsticks enthusiastically, we squealed delightedly over handmade decorative tops signifying the fillings…duck, broccoli, pumpkin, but the most electrifying was yet to come…

Heavy velvet curtains opened dramatically, revealing an opulent royal court complete with Emperor, bejeweled costumes with headdresses and ancient stringed instruments. Swirling colours, haunting music and elegant dances transported us into the grace and beauty of the Tang Dynasty, China’s Golden Age. As totally spectacular as this whole day had been, we quickly discovered that the next day would be even more astonishing.

Beyond Xian’s walls, we rolled out past farms, orchards and roadside stands sun-drying persimmons. Pointing through the bus windows, Hanson remarked, “Imperial tombs surround Xian… emperors, empresses and high-ranking officials are buried there.” Looking at the distant mound of first Emperor Qin Shihuang, we visualized his massive underground burial chamber, described in early records as jewel-filled palaces littered with gold and silver statues, pearl-encrusted ceilings and flowing mercury-rivers, wondering whether the fabled treasures remain in his unexcavated tomb.

He continued, “Ascending the throne at 13, Qin unified ancient feudal kingdoms, establishing China’s first dynasty in 221BC. Seven hundred thousand artisans worked on his mausoleum for decades before his death, never finishing it although his son continued the work as his father wished.”

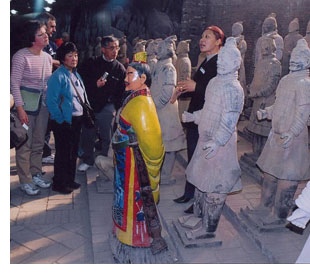

At a state workshop-stop, we watched artisans creating souvenir soldier replicas in many sizes. Examining molds, tools and fire-pits revealed clay-figure secrets. “Terracotta is baked clay,” the guide instructed. “Feet and legs are solid, bodies and heads hollow.” She continued, “Hairstyles distinguished ranks… topknots to the right were soldiers; topknots on the left, kneeling archers; two topknots…like a butterfly…indicated generals; a flattop, officers or horsemen.”

At a state workshop-stop, we watched artisans creating souvenir soldier replicas in many sizes. Examining molds, tools and fire-pits revealed clay-figure secrets. “Terracotta is baked clay,” the guide instructed. “Feet and legs are solid, bodies and heads hollow.” She continued, “Hairstyles distinguished ranks… topknots to the right were soldiers; topknots on the left, kneeling archers; two topknots…like a butterfly…indicated generals; a flattop, officers or horsemen.”

Expecting natural terracotta-earth-tones, I was surprised to learn that hair, eyebrows, faces and hands had been painted life-like colours: pink flesh, white eyeballs, black hair. Yellows and scarlet covered Emperor’s robes, green, soldiers’ trousers. Inspired, my hubby bargained for an entire clay regiment to guard our sunroom plants at home.

Before viewing the revered Army of the Terra Cotta Warriors And Horses, we passed an elderly farmer signing keepsake books documenting his legendary discovery. While digging a new well in 1974, Mr. Yang uncovered bronze weapons and broken warrior-bits, never expecting his accidental discovery would result in this riveting World Heritage Site.

Over the next two years, three earth-and-timber underground vaults were excavated: over one-thousand soldiers discovered in a smaller chamber, sixty-eight warriors and war-chariots in another, the command post. The largest pit had yielded an astounding terracotta army of six thousand life-sized foot soldiers, cavalry and officers.

Inside that bright, air-conditioned pit a football field and a half in size, we could scarcely believe that we were actually witnessing the twentieth century’s premier archeological discovery. The remarkably preserved force stood in battle formation guarding Qin’s ancient imperial necropolis, exactly as he had dictated 2000 years before. Ranging from 5-feet-8inches to 6-feet in height, the armored warriors wore short chain-mail coats, belted long-sleeved gowns, leggings and laced boots. Stretching row-upon-row four abreast, they once held bows and arrows, swords or spears. Although buried for centuries, the weapons were rust-free and still sharp when unearthed.

Hanson observed, “Soldiers and horses have been carefully reassembled from collapsed rubble…and have mostly faded.” From each warrior’s facial expressions, including wrinkles on generals, we imagined their different personalities. Last of all, we paused thoughtfully at the well that had started all the notoriety.

Xian’s celebrated attractions completely captivated our imaginations, resonating still as remarkable memories.

About the author:

Chris Millikan is a freelance travel writer who lives in North Delta, a suburb of Vancouver BC on Canada’s West Coast.

The photos:

1: Six thousand terracotta soldiers stand on guard in pit number one. A World Heritage

Site since 1984. Chris Millikan photo.

2: Lighting candles at the Great Wild Goose Pagoda. Chris Millikan photo.

3: Emperor replica at the State Workshops show colors once used on the terracotta

figures. Rick Millikan photo

Leave a Reply