by Joanne Lane

I am yakking in a yurt about yaks.

I am yakking in a yurt about yaks.

Outside an icy wind is blowing so we’ve gathered around a fire made from yak dung. This keeps the yurt surprisingly warm and no, it doesn’t smell.

We have warm blankets, lots of chay (tea) made from yak milk and plenty of good conversation that does venture beyond yaks. And when it’s warm enough we can lift up the heavy felt door and enjoy one of China’s best vistas over the angelic blue Lake Karakul and its surrounding glaciers. What more could you want?

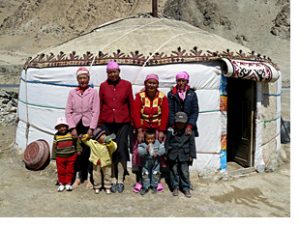

My hosts are a Kyrgyz yurt dwelling family who live by the lake on the Karakoram Highway in China’s far west Xinjiang province. For traveler’s it has become accepted practice to “yurt it” in their tents before continuing over the border to Pakistan or back to Kashgar in China.

Getting here is all part of the fun. From Kashgar the road to Pakistan is windy, dusty and dry. Camels graze by the long straight road, a Chinese masterpiece in such hostile territory, otherwise the only other vehicles are donkey carts with grizzly passengers carting sheep to market.

The towns out here are frontier-like with a mix of Uigur, Han, Pakistani and Kyrgyz people lumped in a corner between their respective borders.

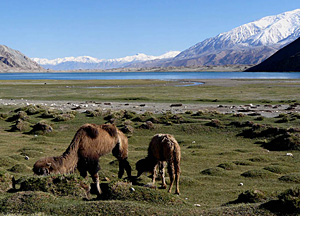

The Karakoram Highway leads through river gorges, barren sand dunes and high mountain passes which are all equally stunning, but the sudden appearance of the alpine lake is remarkable. It’s a huge blue expanse beneath the Pamir Mountains, with the highest peak of Mount Muztagata a dazzling 7546m with slopes flanked with glaciers.

In the valley around the lake, grasslands extend in each direction. Yurts cluster on the grassy fringes and yak, sheep, donkeys and horses make the most of the grazing land. Several yak belong to Abidi, the head of my host family, who lives in one of the yurts with his wife Raspu and their sons Booinish (five years) and Kutush (three years).

In the valley around the lake, grasslands extend in each direction. Yurts cluster on the grassy fringes and yak, sheep, donkeys and horses make the most of the grazing land. Several yak belong to Abidi, the head of my host family, who lives in one of the yurts with his wife Raspu and their sons Booinish (five years) and Kutush (three years).

Abidi is a blue-eyed, fair skinned man of 30 years who met my bus when it arrived at Karakul. He had some English but it was the flowery recommendation he had flourished written by some fellow travelers of his family’s yurt life that convinced me.

A day in a yurt begins with chay (tea) and bread by the fire. A fire is needed all year round, because at 3800m the weather is freezing even in summer and there can be snow showers into June.

Abidi’s yurt is about 10 metres across. A stove for cooking and heating lies just inside the door with a pipe that goes out through an opening in the ceiling that can be widened or closed depending on the weather. Cooking utensils and pots are stored inside near the stove.

The floor beyond is covered with brightly woven mats and carpets. It’s a simple life but it’s also clear the family prefer this to living in the village, where they move when it becomes too cold.

Yurt life must be hard collecting water daily and sleeping on the floor, but there are also glimpses of the idyllic. Raspu and the other yurt women spend the day sewing on blankets outside while the kids play. It must be one of the best views of any workplace in the world. They are also in a happy position to spot passing tourists and offer them shelter, food or handicrafts for a haggled price.

On a sunny day it is particularly pleasant sitting outside, although generally yurt families are unphased by the cold and the younger kids have slits in their pants for quick toileting – a quick but surely cold method of potty training. The official toilet amounts to a designated area under a cliff face and the lake is used for washing – a chilling experience even to clean your teeth.

Once the sun sets time outside is minimal apart from the obligatory sunset shots. These are suitably gorgeous and if the cold doesn’t take your breath away the scenery will. Dusk is magic as the locals call their yak in for the night, Abidi’s sons chase goats and horses as take take their last tugs on the grass.

In the evening the family spends their time in conversation and song around the fire. While they’re aware of the upcoming Olympics they aren’t too concerned about the issues surrounding it. They are Kyrgyz and Beijing is many miles away.

During the day walking opportunities abound – simply strike out across the grasslands or climb one of the small hills for aerial views. The climbing can be tough in the high altitude but well worth it. The glaciers can be climbed but you should arrange a local guide and equipment. The locals also offer motorbike, horse or camel tours.

During the day walking opportunities abound – simply strike out across the grasslands or climb one of the small hills for aerial views. The climbing can be tough in the high altitude but well worth it. The glaciers can be climbed but you should arrange a local guide and equipment. The locals also offer motorbike, horse or camel tours.

Abidi and I circumnavigated the lake by motorbike one morning. It was an innovative tour starting with a visit to his sister-in-law for yak milk tea and hot bread. Then we visited the dusty village school and mosque. Finally we drove around the lake admiring the flowers and passing yak, camel and horse.

Iif you don’t want to be this active you could draw, write, read or snooze and still feel you’d made the most of the day. Life operates at its own yurt-like pace – it’s all about the movement of yak, a good dung fire and hot cup of tea. Time doesn’t stand still but it’s certainly a happy illusion.

About the author:

This week Traveling Tales welcomes freelance travel writer Joanne Lane who lives in Queensland, Australia;

Photos by Joanne Lane:

1: Women and kids pose out side a yurt..

2: Camels roam near Lake Karakul.

3: My host Abidi on his bike.

How To Get There:

Three buses depart daily from Kashgar for Lake Karakul (Y 40-50). Kashgar is connected to other parts of China by train, bus and air. The Caravan Cafe on Seman Lu can organise tours and onward travel. Kyrgyz yurt dwellers will meet the bus on arrival at Karakul.

Many have written recommendations in several languages and charge Y20-30 per night including food. Avoid staying in Jungking village which charges Y40 to enter the village. Mr Abidi Kudush lives one kilometre from the bus stop in a small clump of yurts by the lake. To contact him phone 1377 961 7293 from Kashgar, but get a local to talk on your behalf for better communication.