by Joan Fitting Scott

In 2004, some 3.2 million visitors made the pilgrimage to the 1,200 square miles of stunning, protected wilderness that is Yosemite National Park, high in California’s central Sierra Nevada range. Contrast this to about 380,000 recreation visits the same year to Lassen Volcanic National Park, another of California’s truly majestic alpine sites, and you might head in a different direction for your next California mountain vacation.

In 2004, some 3.2 million visitors made the pilgrimage to the 1,200 square miles of stunning, protected wilderness that is Yosemite National Park, high in California’s central Sierra Nevada range. Contrast this to about 380,000 recreation visits the same year to Lassen Volcanic National Park, another of California’s truly majestic alpine sites, and you might head in a different direction for your next California mountain vacation.

We did.

Snow arrives early at Lassen, which is tucked into the far northeast corner of the state. And it stays late.

While snowshoe programs are available to the public from early January through mid-March, the park operates with full services just three glorious summer months—as opposed to Yosemite, which has year-round full service. That and its relatively remote location account for Lassen’s status as one of America’s less crowded national parks.

Located near Mineral, California, population 90, at the southern end of the Cascade Range, the park is situated at the juncture of those mountains, the Great Basin desert to the east and the Sierra Nevada range to the south.

Lassen preserves 106,372 acres of lakes, forests, and amazing geological and hydrothermal phenomena. All four types of volcanoes found in the world are represented here, as are over 700 species of flowering plants and 250 vertebrates.

During our visit my family and I soaked up the exquisite scenery and ogled things that boiled, gurgled, hissed and steamed—they have names like Devastated Area and Devil’s Kitchen. One of the park’s evocative names graces Bumpass Hell.

We hiked five wildflower-filled miles round trip to this, the park’s main geothermal area, named for a mountain man who fell into a thermal pool, burning his leg so badly it had to be amputated.

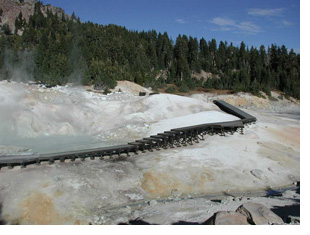

We arrived to the rotten-eggs smell of hydrogen sulfide. Walking across catwalks designed to protect us from the heat of this natural cauldron, we gazed down at boiling mud pots and superheated steam vents. Their colors astounded us—ochre, aqua and every shade of gray.

We arrived to the rotten-eggs smell of hydrogen sulfide. Walking across catwalks designed to protect us from the heat of this natural cauldron, we gazed down at boiling mud pots and superheated steam vents. Their colors astounded us—ochre, aqua and every shade of gray.

Next we scaled the heights, climbing 10,457 foot-tall Lassen Peak. Our trek took us two and a half miles and 2,000 feet up to an extravagant view of the Warner Valley and Lake Almanor below. We hiked up and back in about three and a half hours. Perhaps 30 to 50 people climb the slope on a summer day—far fewer than at nearby Mt. Shasta.

Both of the park’s pasts—the ancient one and the more modern one—tell a gripping story. Picture-perfect lakes and the seemingly serene mountain from which the park takes its name belie fiery beginnings 600,000 years ago.

Both of the park’s pasts—the ancient one and the more modern one—tell a gripping story. Picture-perfect lakes and the seemingly serene mountain from which the park takes its name belie fiery beginnings 600,000 years ago.

At that time, the clash of continental plates led to savage eruptions and the formation of Mt. Tehama, some 11,500 feet tall and 11 miles across. Lassen Peak began as a vent on Mount Tehama’s flank. While Tehama eventually collapsed, Lassen Peak remained.

Fast forward to the nineteenth century and along come some mighty interesting characters. California’s 1848 gold stampede ushered in some of the area’s first settlers.

One of them was the man for whom the park is named, Peter Lassen. A Danish immigrant, he arrived here by mistake. Old Pete found the area that is now the park after getting lost while guiding a group of emigrants; their trail is still visible in places.

Of course, the Indians had always called this spot home. For the Maidu, Yana, Yahi and Atsugewi, the area served as a meeting point. They camped here in warmer months, but left when the snows came.

One of their descendents, the now-famous Ishi, turned up in Oroville, California in 1911. A member of the Yahi tribe, thought to be extinct, he is considered to be the last Stone Age survivor in America. Ishi, whose name perhaps signified “man” in his native language, ended his days as an ethnological resource at the Anthropology Museum of the University of California.

Lassen’s elevations range from 5,000 to better than 10,000 feet, so its habitats are many. One hundred and fifty miles of trails (including 17 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail) and a scenic highway uncluttered by carloads of nature lovers allowed us see them. It took us about three hours to drive through the park; that included stops to take in its amazing scenery.

If you choose the quiet beauty of Lassen next summer over more hectic spots, you’ll need the better part of two days to hike the park.

There are several camp sites available for overnight stays. The campgrounds at Manzanita Lake make a good place to stop for the night; here you’ll find a boat launch, fishing, and swimming.

If you prefer not to camp, lodging near the park is rustic, but not without charm. Accommodations can be found in nearby, nearly empty Mineral at Lassen Mineral Lodge. Rooms are inexpensive and spartan, but located in a stand of fragrant evergreens. Dinner is served either inside or al fresco.

Thirty miles away is the town of Chester and neighboring Lake Almanor; both offer a range of accommodations and restaurants.

Lassen Peak is what geologists call an active dormant volcano, and could blow at any moment.

The last time it let loose was as recently as 1914. Then it sent a cloud of debris some seven miles upward—thus the names conjuring up images of devilish destruction. Seismologists promise to let us know ahead of time should the mountain be ready to vent again.

Some say that might be soon. Make your plans now.

About the author:

Joan Fitting Scott is a freelance author and travel writer who lives in Forth Worth, Texas.

About the photos:

1: Viewing a giant crater at Lassen National Park. Walter Zischke photo.

2: Catwalks allow visitors to cross steaming hydrothermal pools. Joan Fitting Scott photo.

3: One of the super-heated vents. Joan Fitting Scott photo.

If you go:

For help planning your trip, visit www.nps.gov/lavo, or call (530) 595-4444.