Story and photos by Antonia Malchik

I had imagined Provence as beautiful, gently refined, and hypnotic. I planned on spending four days there stupefied with food and wine, rolling through the purple visage of lavender fields. Instead, I found a harsh, vertically-defined landscape.

This was not the France of gentle postcards and feast-filled guidebooks. This was Haute Provence, the 1900-square-kilometer Geological Preserve where gorges sliced through crazed mountains and made driving a roller coaster adventure.

We’d driven up 200 kilometers from Nice. Ian, my husband, had little experience driving a manual car, so the tiny-engined Opal Corsica was in my terrified hands. A narrow highway cutting through dark mountain passes, the road constricted even more to sidle through long tunnels. I couldn’t get used to the French idea of treating the highway as a single lane, moving to one side only when a car came the other direction.

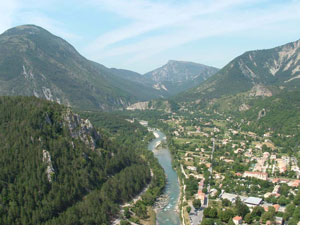

When we finally arrived in Castellane, I pulled the handbrake with a weak, shaky jerk. As I recovered enough to look around, white-knuckled fear left and simple admiration remained. The tiny town guarded the entrance to the Gorges du Verdon, (also known as ‘Grand Canyon du Verdon’) a gorge 21 kilometers long, the Verdon River racing along the bottom.

When we finally arrived in Castellane, I pulled the handbrake with a weak, shaky jerk. As I recovered enough to look around, white-knuckled fear left and simple admiration remained. The tiny town guarded the entrance to the Gorges du Verdon, (also known as ‘Grand Canyon du Verdon’) a gorge 21 kilometers long, the Verdon River racing along the bottom.

An ancient church brooded high on a cliff top overlooking Castellane’s center, a place of colorful shuttered buildings that I never would have heard of if it hadn’t contained the only available hotel rooms in July. And we were lucky to get those.

“This place is packed,” grumbled Ian the next morning. I’d dragged him out without enough coffee, insisting that fresh air would wake him up. Dutch, German, and French tourists on elongated summer holidays strolled and raced (depending on age) to the cliffhanging, fenced-in scenic overlook.

The view tumbled 700 meters to a glacier-blue river that wound through the gorge, on its way from one dam-made lake to another, both out of sight. While kids squeezed through the fence to hang out over the shrubby cliff, I stood well back, safely against a boulder. I could deal with heights; it was just my knees that dissolved.

The magnificent view wasn’t what we’d come to see. A steep trail ran from the parking lot where we left the car, down to the river, along its bottom, and back up again at the other end. We backtracked to the trailhead, hidden among trees and shrubs that blocked any view, but the other tourists also disappeared.

Halfway down, Ian and I tucked ourselves under a rock overhang and ate the Brie, baguette, and mandarins I’d bought that morning. A pair of slim, muscular men powered up to us from below. They’d hiked into the gorge from the opposite end.

“Very nice,” said the younger one in German-accented English, running his hand through stubby brown hair. “Nice spot. You go all the way?”

“No,” I said. “We started too late.” In the cool, clear morning, it had been tempting, as always, to swing sleepily by the scenic overlooks and drive on to a soporific lunch, but Verdon had views that could only be seen on foot.

“Plenty of time,” they said when we asked if we had time to walk along the river bottom. “It’s not so late.” The two men hefted their packs and powered back uphill. We, lazy and office-worker soft, lumbered downhill more slowly.

When we arrived at the river some time later, tourists popped up again, younger and fitter than those at the top of the gorge. Teams of active twenty- and thirty-somethings huddled around a lumpy, boulder-filled area that served as a beach and picnic spot. They cheered as the rest of their companions body-surfed down the rapids.

The Verdon River, which was dammed, could rise several feet within seconds, guidebooks warned; these adventurers could only traverse it in guided groups. The water cooled my feet before we entered the tunnels and quiet trails that snaked alongside the river.

Between hiking and sleeping, Castellane’s minor distractions were sufficient, although it had limited attractions for the culture-seeker. Its little restaurants were few but excellent, a cliché of French cuisine. “Twelve manner snails burgundy” and “Cobblestone of Sandre to the white butter” turned out to be exquisite, melting morsels, easily translatable to the palate if not into English.

The day before we left, we hiked up to the lady of Castellane, the eighth-century church on the cliff, Notre Dame du Roc. Its ancient path wandered up the backside of a mountain through the ruins of a monastery.

The day before we left, we hiked up to the lady of Castellane, the eighth-century church on the cliff, Notre Dame du Roc. Its ancient path wandered up the backside of a mountain through the ruins of a monastery.

“Imagine,” I puffed, as I scrambled on the steep slope, “having to trek up here every day, carrying supplies and trying to push a donkey along.” We reached the top with our hearts pounding.

We looked out over the cliff’s view, a vista I could appreciate a good distance from the edge. Castellane, shuttered by mountains, its only outlet along the narrow road or the escape of the river, looked even smaller from above.

No, it wasn’t what I had imagined I would find in Provence. Its rugged beauty was more rewarding by far.

The only disappointment was the lack of lavender fields. Little shops and roadside kiosks sold the requisite lavender seeds, lavender honey, lavender pillows, and pictures of the purple fields, but we had to drive a long way through the Geological Preserve to find just one small, entrancing lavender field bordering a stone house.

The only disappointment was the lack of lavender fields. Little shops and roadside kiosks sold the requisite lavender seeds, lavender honey, lavender pillows, and pictures of the purple fields, but we had to drive a long way through the Geological Preserve to find just one small, entrancing lavender field bordering a stone house.

“We should grow lavender like this,” said Ian. “Hundreds of them.” I looked at him. We lived in wetlands. Only water grasses grew easily by our house. Lavender, like all Mediterranean herbs, needed lots of sun and well-drained soil. This sunny purple field, preserved in a photo, would have to do. But its importance as a symbol of Provence had dwindled for me, buried under the extreme mountains and gorge-defined roads.

About the author:

This week Traveling Tales welcomes Antonia Malchik, a freelance travel writer living in upstate New York.

Photos by Antonia Malchik:

1: Overview of the town of Castellane.

2: The Lady of Castellane, an eighth century church atop Notre Dame du Roc.

3: Our camera records a memory of Lavender fields.

More Information

How to Get There: In Canada, flights to Paris are routed through Montreal or Toronto; it’s then a short hop to Nice, which is the closest major airport to Les Gorges du Verdon. From the US, the cheapest flights to Paris are from the East Coast. To include the Geological Preserve in a tour of Provence, you can also fly into Marseille. Provence is best visited in a car. There is little or no public transport. Castellane is about 200 km from Nice, through Cannes.

Where to Stay and Eat: The Hotel du Commerce in the main square is the most up-market hotel. We stayed at the Grand Hotel du Lamont, basic but cheap at about USD40 a night.

Europeans often stay in campgrounds just outside of town. However, speaking to a few of them, I found that our hotel was slightly cheaper, and they complained of poor-quality fast food at the campsites. Altogether, it’s nicer to stay in town and walk to dinner.

Hotel du Commerce has the best restaurant in town (without Cobblestones of Sandre), worth a celebratory night out. La Main a la Pate on the main square serves three excellent, cheap meals a day. Since the town is small, it’s easy to walk to the bakery, the small supermarket, and the several restaurants for your noshing needs.

What to Do: The tourist information office just off the main square has ample hiking maps and information about reaching trail heads by a local hiking bus. To cool off, the dam-made Lac de Castillon is just over the valley from Castellane, and has designated beaches.

Parts of the Verdon River are accessible to canoeing and rafting groups, subject to the dam’s activity at the time. You can also go rock-climbing and horseback riding. All information is at the tourist information office.