by Margaret Deefholts

From where I sit perched on my elephant howdah, the Kaziranga National Park is a stretch of wild grassland fringed by marshland and thick jungle. The mahout nudges me gently and points.

Fifty feet away, small ears flicking, and horns pertly upturned like inverted commas, two one-horned rhinos stand face to face as if in conversation. One of them turns its head and peers short-sightedly at us through little piggy eyes.

Fifty feet away, small ears flicking, and horns pertly upturned like inverted commas, two one-horned rhinos stand face to face as if in conversation. One of them turns its head and peers short-sightedly at us through little piggy eyes.

I freeze and so does our elephant. Rhinos are notoriously unpredictable and have been known to charge with amazing speed despite their tank-like size.

But perhaps camera-toting tourists have become a ho-hum sight these days, or the wind has changed direction. Either way, the rhinos lose interest in us and lumber off in the direction of a muddy watercourse.

Located in Assam, in the north-east corner of India, the 430-acre Kaziranga Park is a rare success story in the annals of animal conservation.

Other than the Chitwan Reserve in Nepal, Kaziranga (declared a national park in 1974) is the only place in the world where one-horned rhinos (Rhinoceros Unicornis) are still in existence.

Although they remain an endangered species, they were on the verge of extinction thirty years ago having dwindled down to less than 200 animals in both India and Nepal.

Today, the rhino population in Kaziranga hovers around the 1700 mark. Even so the battle against poachers is far from over. Rhino horn—actually a spike of hardened hair—is reputedly an aphrodisiac and, as a powder it sells for about $40,000 per kilo.

The dawn is misty until an enormous, blood-orange sun emerges suddenly over the horizon. A swamp deer with curving antlers leaps across a field and for an instant is silhouetted against the sun like a black cardboard cut-out.

The breeze carries the tang of marshland, and as we emerge from a thicket of twelve-feet high spiny grass, we catch sight of a herd of wild elephants about a hundred yards away wallowing in the mud. A mother playfully squirts her baby with a stream of water. Engrossed in their morning toilet, they ignore us.

The breeze carries the tang of marshland, and as we emerge from a thicket of twelve-feet high spiny grass, we catch sight of a herd of wild elephants about a hundred yards away wallowing in the mud. A mother playfully squirts her baby with a stream of water. Engrossed in their morning toilet, they ignore us.

Not so a family of wild buffalo. They have a calf in their midst and the male lowers his head and tosses his horns. Our elephant hastily backs away.

An estimated 53 tigers also prowl through Kaziranga, but are tough to spot as they blend in with the tall, tawny grassland. The mahout shakes his head when I ask him about the possibility of a sighting. “Not here,” he says emphatically. “The jungle grows very quiet when a tiger is around.”

The morning is anything but silent: a cloud of chittering mynah-birds swerve and scatter overhead and the whoop of a langour monkey floats across to us from beyond a fringe of trees.

Later that day Palesh, a young man with an encyclopaedic knowledge of Kaziranga’s bird population, takes me on an open-roof jeep along rutted jungle paths. “Stop! Stop!” he commands the driver at intervals, and points out the flash of a small blue kingfisher, a pompous-looking spotted owlet and shoals of partridge.

An egret rides on the back of a rhino, and nesting lesser adjutant storks regard us with hauteur. Kaziranga boasts approximately 480 species of birds, some of which are migratory, and in a ninety-minute drive we spot at least 40 varieties—crow pheasant, red-breasted parakeets, a racquet-tailed drongo and a Pallas fishing eagle, to name just a few.

Back at the Wild Grass Resort I sit in the garden by the swimming pool. As dusk falls crickets shrill in the hibiscus bushes and an Indian Koel bird sends its plaintive cry across the lawns—a harbinger of summer.

The sunset sky is streaked orange and purple. Tomorrow I will be back amid the seething crowds of Mumbai—but will carry with me memories of emerald parrots, petal-eared rhinos and the eerie yowl of jackals under the full moon.

About the author:

This week Traveling Tales welcomes Margaret Deefholts, an author and freelance travel writer who lives in Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver B.C. Learn more about Margaret at her website www.margaretdeefholts-journeys.com

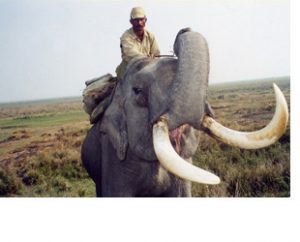

Photos by Margaret Deefholts:

1: Curious one-horned rhino

2: Welcome Salute by Tusker

3: Wild Grass Resort

Best time to Visit: Between November and April. Closed during the monsoon – June to September. The winter months from November to February are cool and require light woollens. March and April are steamy.

Getting There: Gawahati, the nearest city to Kaziranga has air connections from all the major Indian cities, after which it is a 5 ½ hour road trip to get to the game sanctuary. Although State transport buses ply from Gawahati, the most convenient way to get there is by private tourist taxi. Most operators offer reasonably priced services.

Accommodation: Wild Grass Resort offers safari tours and luxury accommodation. For more information visit www.nivalink.com/wildgrass/index.html

For More Information: www.kaziranga-national-park.com/hotels-resorts-kaziranga.shtml