|

||

| Arizona's Other Canyon

By Karyn Zweifel |

||

Breathtaking.

Spectacular. Awe-inspiring. It's no wonder the Grand Canyon is one of the world's

most visited spots. But another Arizona landmark, 235 miles to the east, had an

equal yet different capacity to steal my breath away and inspire quiet reverence. Breathtaking.

Spectacular. Awe-inspiring. It's no wonder the Grand Canyon is one of the world's

most visited spots. But another Arizona landmark, 235 miles to the east, had an

equal yet different capacity to steal my breath away and inspire quiet reverence.

It's the Canyon de Chelly (pronounced "de-shay") near Chinle in the Navajo Indian Reservation. Canyon de Chelly National Monument is actually a series of canyons tucked away in the eastern edge of Arizona. Driving there, it's easy to draw a parallel between the bleak and treeless landscape and the apparent poverty of the Navajo people. But looking closer, the desert is teeming with life on an unexpected plane. Canyon de Chelly, with its prehistoric pictographs, Anasazi ruins and current-day Navajo residents, offers a glimpse back in time at an endangered culture. It's also a vacation stop relatively uncluttered by cheap gift shops, oversized tour buses and hordes of tourists. We arrived late in the day, and drove to the overlook for the largest and most accessible canyon, Canyon de Chelly.

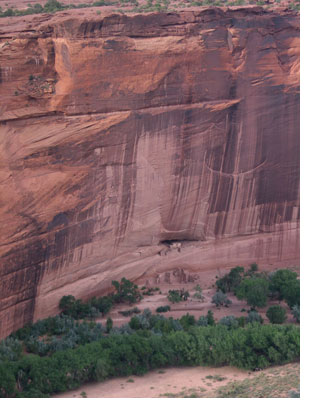

A childlike figure is just visible, bent over a row of plants at the canyon floor. Far away on the northern wall of the canyon is a gap in the stone, gradually widening. Only with the help of binoculars do the ancient stone dwellings tucked inside the wall become apparent. They look like toys, or even painted false fronts, hardly likely to have sheltered up to 80 people. Next morning, the dawn breaks over a perfectly clear sky, a little breeze kissing at our heels as we begin to descend into the canyon. The trail is wide and easy, a gentle grade switching back and forth as it lazily winds down some eight hundred feet to the canyon floor. Only an hour after sunrise the sun begins to bear down, and it is with relief that we reach the shady canyon floor. The National Park Service manages the area in cooperation with the Navajo Nation. Because of the cultural and spiritual significance of the ruins and the fact that Navajo families live and make a living within the canyons, unescorted visitors are limited to a single moderately easy hike within the main canyon to the periphery of the White House ruins. To explore the park in more depth, visitors have to apply for a permit and hire a guide.

Enclosed within a wire fence are a few crumbling walls, suggesting a sizable three-story building whose roof and floors are long collapsed. The dwellings were built about a thousand years ago, before the Navajo came, and abandoned inexplicably three hundred years later. The more recent Navajo residents call the original builders "Anasazi" or "ancient ones." Beyond these ruins, seventy five feet or more above the canyon floor, a cluster of adobe buildings is tucked into a deep crevice. Barely visible beyond the first row of dwellings is a nondescript rectangular whitewashed structure with deep religious significance. A Navajo healing ceremony, nine days long, mentions the "white house" where the thunderbird god lives, a "place between." These ruins, like others in the park, are facing south to take advantage of the sun in the long winter months. The park holds many other sights, including famed Spider Rock, the Canyon del Muerto (Canyon of Death), Antelope House ruins and Massacre Cave. But the Arizona sun promises to be pitiless, and we straggle back up the trail and retreat to air-conditioned comfort. When afternoon shadows stretch long across the canyon, we return on horseback with a native guide. Edwina is eighteen and not very talkative. She points out a handful of petroglyphs, graphic, evocative stick figures of people and animal scratched deep into the wall. Our six-year-old son gets more pleasure from seeing animal shapes in distant rock formations at the top of the canyon: a turtle, a rabbit. The horses are swaybacked, pestered by flies. We ride for an hour and return to the stables. They are shabby, with a broken down couch shoved haphazardly onto the porch of an adjoining house. A band of small children peer around the corner and a baby wails inside. Outward signs speak of hardship. But perhaps this is deceptive, like the view of the canyon floor seen from the rim. This is a culture that has inhabited this particular corner of the world for three hundred years, following the Anasazi who were here for thousands of years before. They are a people with a different rhythm, different values, a different perspective. While it is tempting to dismiss the experience with a flicker of pity and a dash of charity, we can't. Instead we climb into our car and point ourselves east, back to our own civilization, wondering if relics of our own culture will hold as much meaning in a thousand years, or even survive at all. This week Traveling Tails welcomes freelance travel writer Karyn Zweifel an author and writer living in Birmingham, Alabama. Visit her website at www.karynzweifel.com and learn more. About the photos: |

The

canyon walls are sheer and sculpted from a subtle palette of sandstone, ranging

from a dramatic red to a pale beige with a rosy tint. The scale of the canyon

tricks the eye.

The

canyon walls are sheer and sculpted from a subtle palette of sandstone, ranging

from a dramatic red to a pale beige with a rosy tint. The scale of the canyon

tricks the eye.  Now our path is level, cutting past an orchard of gnarled old

trees, over rock outcroppings and even through a short tunnel cut through the

rock. We come out through the trees to a plain dotted with trees and stretching

a few thousand feet to the sheer rock face.

Now our path is level, cutting past an orchard of gnarled old

trees, over rock outcroppings and even through a short tunnel cut through the

rock. We come out through the trees to a plain dotted with trees and stretching

a few thousand feet to the sheer rock face.