|

||

| TURTLE TREKKING - IN SEARCH OF COSTA RICA'S ARRIBADAS

Story by Cherie Thiessen Photos by Casa Romantica |

||

Beneath

a dense black ledge of clouds a full moon hoists itself above the horizon, revealing

the best place to cross the swollen rivers. We can’t believe our luck. The

downpour that has assailed us since dawn, has stopped just in time for our trek

along this deserted beach. There are four of us following our guide, Jorge: myself,

my partner David, and our close friends Heather and Eric. Jorge has gone on ahead

and we’re to follow if and when he signals with his flashlight. Beneath

a dense black ledge of clouds a full moon hoists itself above the horizon, revealing

the best place to cross the swollen rivers. We can’t believe our luck. The

downpour that has assailed us since dawn, has stopped just in time for our trek

along this deserted beach. There are four of us following our guide, Jorge: myself,

my partner David, and our close friends Heather and Eric. Jorge has gone on ahead

and we’re to follow if and when he signals with his flashlight.

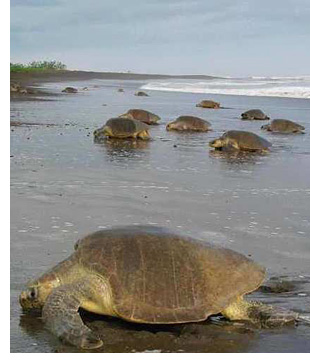

Fringed by a jungle of palm trees on one side and the Pacific surf on the other, and intersected by numerous rivers, Ostinal Beach on Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula is one of the world’s most famed “arribadas” beaches. Here, four to 10 times a year between July and November, Olive Ridley turtles trundle ashore by the thousands to lay upward of 80 eggs each before returning to the sea. Thirty-five to 40 kilograms in weight and 60 to 75 millimeters in length, an Olive Ridley may be one of the smallest of the world’s marine turtles, but it’s still plenty big enough to stub a toe on.

October is a risky month to travel Costa Rica’s roads. Impassable at the best of times, they are also bereft of directional signs. In the “Green Season”, the local euphemism for the May to mid-November monsoons, the country’s back roads turn into truck-sucking quagmires traversed by marauding rivers. We’d left our Samara resort at daybreak, allowing five hours to drive just 50 kilometres. We’d also tried to locate a guide and a place to overnight at Ostinal, but the translated messages were vague. Something about the Nosara River being impassable by car . . . and “Si, Si”, someone might meet us on the other side of the river to take us into Ostional and arrange for a licensed guide. Five hours later, the sheeting rain had slowed us to first gear and rendered all possible sources of directions invisible. Were we even on the right road? When a raging river appeared suddenly in front of our windshield, we were ecstatic; at long last, the Nosara, We backtracked to a nearby farmer’s home, arranged to leave our car in his field for a small fee, and then set off on foot back to the river with umbrellas, backpacks and uncertain spirits. The farmer had indicated we could cross on a footbridge a half-mile further. The blood-curdling roars of howler monkeys followed us as we slithered through the mud and over the footbridge, our hoped-for rendezvous point.

Sure enough, at 10 PM, Jorge arrived and led us down a lonely stretch of beach. Now our eyes strain for a sign that far ahead, he’s tracked down a Ridley. He has. The light flashes, and we hurtle forward, eventually to make out tracks leading from the sea to the banks of a rivulet. And yes, there’s our valiant mamma Ridley trying to climb the crumbling bank. Programmed to return to the same stretch of beach each year, she has tumbled down the bank several times, unable to reach her destination. Jorge raises her up and over. She hesitates, crawls a short distance, and then seems to know she’s home. She begins to dig with her back flippers.

An hour later, we are still watching as she retraces her tracks, tumbling yet again down the riverbank, until at last she bathes her face in the waves of the Pacific. Walking back, we keep smiling at one another. How will we get back tomorrow? Who knows? Where will we find anything to eat in this tiny village devoid of tourists? Who cares? Stepping off the secure path, we have entrusted ourselves to the kindness of strangers and been rewarded. IF YOU GO: Where to stay Other lodgings, car rentals, and general information: Turtle and Park information: This week Traveling Tales welcomes Cherie Thiessen who landed her dream job as a travel writer at the age of 50, and now writes and teaches travel writing from her Canadian Gulf Islands’ home. Photos by Casa Romantica: 1. Arribadas | ||

| Return To Home Page |

Observing one of

these mass egg-laying phenomena has long been at the top of our must-do list,

but we’ve been following Jorge for an hour and one thing is fast becoming

clear: there will be no arribadas tonight.

Observing one of

these mass egg-laying phenomena has long been at the top of our must-do list,

but we’ve been following Jorge for an hour and one thing is fast becoming

clear: there will be no arribadas tonight.  Across the bridge,

no vehicle in sight. Nothing to do but splash on. Half an hour later, hope was

revived when we saw a filthy pickup making its way toward us. In animated Spanish

the driver explained everything, and we understood not a world. His final gesture

was clear, however. Climb in. We did. After several bumpy miles the sight of yet

another river slicing the road once again dampened our hopes. Our rescuer shrugged

his shoulders and indicated the footbridge we could cross. He could go no further.

On our own again. In a moment he had turned around and was heading back the way

he had come, waving out the window. Again we found ourselves crossing an unexpected

torrent, and squishing onward, but this time our soggy slogging was cut mercifully

short. “Hurray, look!” Another pickup was bouncing toward us. Sloppy

but enthusiastic greetings were shared all around, and then we were herded into

the back of the driver’s open truck. A 15-minute dash through potholes and

mud and we arrived at the village of Ostinal where a room in a hostel awaited

us and our host pointed to his watch, indicating we would be turtle trekking at

10 p.m. As the four of us vowed to study Spanish more seriously next time, we

gave thanks to the power of gestures and to the Gods who had allowed us to bumble

on this far.

Across the bridge,

no vehicle in sight. Nothing to do but splash on. Half an hour later, hope was

revived when we saw a filthy pickup making its way toward us. In animated Spanish

the driver explained everything, and we understood not a world. His final gesture

was clear, however. Climb in. We did. After several bumpy miles the sight of yet

another river slicing the road once again dampened our hopes. Our rescuer shrugged

his shoulders and indicated the footbridge we could cross. He could go no further.

On our own again. In a moment he had turned around and was heading back the way

he had come, waving out the window. Again we found ourselves crossing an unexpected

torrent, and squishing onward, but this time our soggy slogging was cut mercifully

short. “Hurray, look!” Another pickup was bouncing toward us. Sloppy

but enthusiastic greetings were shared all around, and then we were herded into

the back of the driver’s open truck. A 15-minute dash through potholes and

mud and we arrived at the village of Ostinal where a room in a hostel awaited

us and our host pointed to his watch, indicating we would be turtle trekking at

10 p.m. As the four of us vowed to study Spanish more seriously next time, we

gave thanks to the power of gestures and to the Gods who had allowed us to bumble

on this far. The four of us

hug each other. The howler monkeys are back, roaring in the trees, but they no

longer sound ominous. The universe has tipped toward us, and we can’t believe

we are here at last; two hypothermic couples with a pathetic smattering of Spanish

and a non-English-speaking guide, yet we understand. We understand we are blessed.

For two hours, while the moon spills its light and we stand entranced, the valiant

Ridley first pushes her eggs into the deep, funnel-like hole she has scooped out

then covers her eggs with sand. Crying from exhaustion, the Ridley now begins

to rock, but this is no lullaby. She’s gathering momentum for gigantic slams

over the covered eggs, packing the disturbed sand solidly to protect her ‘nest’

from scavengers. These baby turtles will hatch without the comfort of their mother.

The four of us

hug each other. The howler monkeys are back, roaring in the trees, but they no

longer sound ominous. The universe has tipped toward us, and we can’t believe

we are here at last; two hypothermic couples with a pathetic smattering of Spanish

and a non-English-speaking guide, yet we understand. We understand we are blessed.

For two hours, while the moon spills its light and we stand entranced, the valiant

Ridley first pushes her eggs into the deep, funnel-like hole she has scooped out

then covers her eggs with sand. Crying from exhaustion, the Ridley now begins

to rock, but this is no lullaby. She’s gathering momentum for gigantic slams

over the covered eggs, packing the disturbed sand solidly to protect her ‘nest’

from scavengers. These baby turtles will hatch without the comfort of their mother.